'Little Rock Girl 1957' Removed From Marietta Middle School Curriculum

Georgia's Divisive Concepts Law affects how civil rights history is taught.

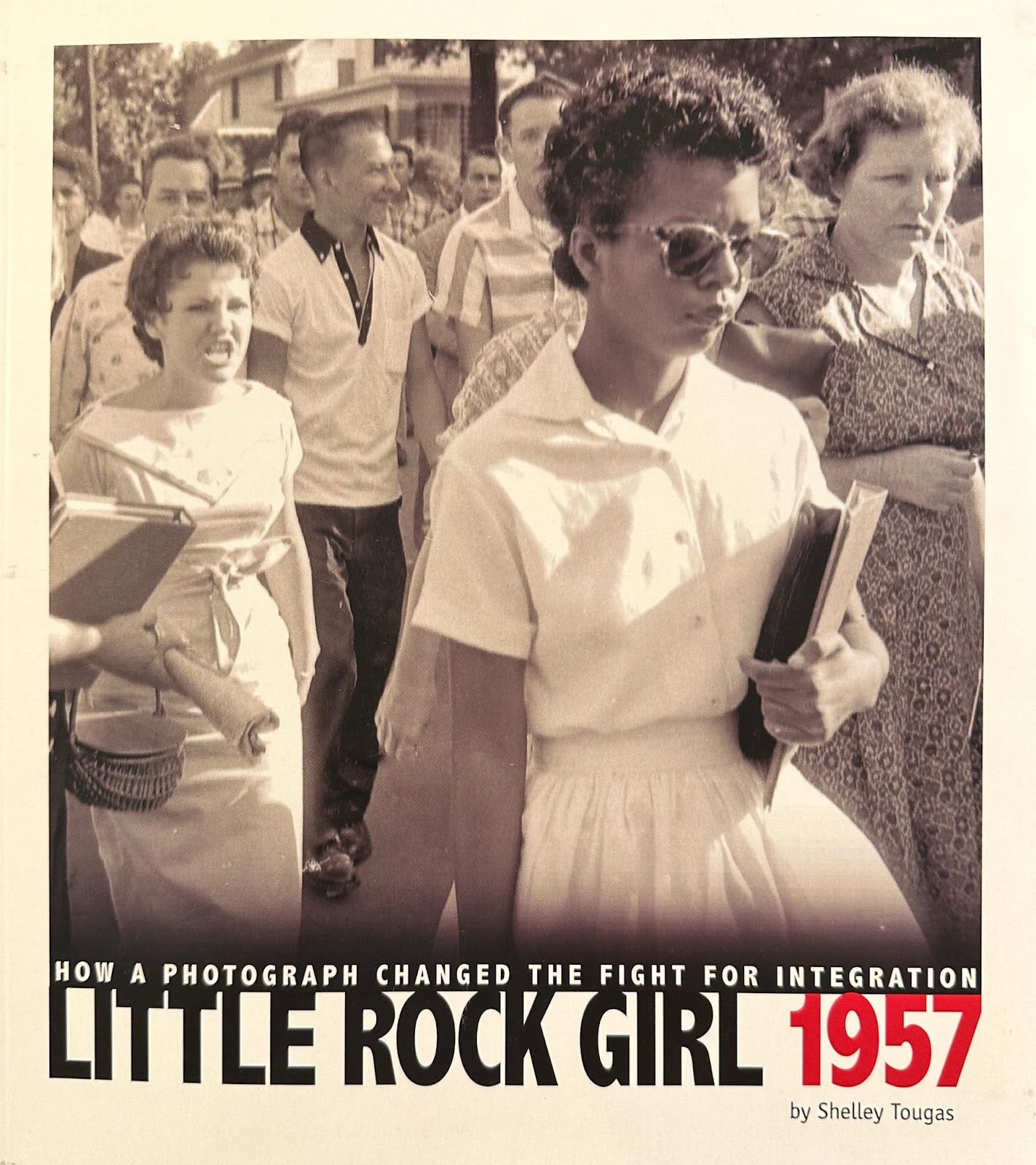

Little Rock Girl 1957: How a Photograph Changed the Fight for Integration is a powerful look at the photograph of Elizabeth Eckford, one of the Little Rock Nine, and how this historic photo knocked a giant crack in the segregationist movement, turning the tide of worldwide public sentiment against the segregationists in the American South.

Just like The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Little Rock Girl has been removed from classroom curriculum at Marietta Middle School and put on the list of Not Approved (for classroom use) books for Marietta City Schools students. Remember, unlike the very public removal of books from the Marietta High School Media Center last school year, mass removal of books from the district’s classrooms has been done quietly away from the public eye. These are separate, but connected issues.

It’s not the only Civil Rights Era book that has been removed. A Mighty Long Way by Carlotta Walls LaNier is on the Not Approved list as well as The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot. Marietta in the Middle is slowly gathering the vetting documents used to remove these books via open records requests, and the details of the vetting document for Little Rock Girl are below. Little Rock Girl and A Mighty Long Way are key first hand accounts of the integration of Little Rock Central High School, and their removal from MCS classrooms is indicative of the way Georgia’s Divisive Concepts Law is being used to change the way important parts of civil rights history are being taught to Georgia students.

After Brown vs the Board of Education in 1954, Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas prepared for integration. The local school board was supportive of integration and Superintendent Virgil Blossom submitted a plan for gradual integration of the schools. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus, a staunch segregationist, sent the National Guard to prevent the first nine students, who came to be known as the Little Rock Nine, from entering the school.

The plan had been for the nine students to enter the school that first morning together, but Elizabeth Eckfords’ family did not have a phone and was not privy to the plan. Elizabeth faced the white mob alone that morning, and as she was trying to enter the school, photographer Will Counts took the famous photo that ran in magazines and newspapers around the world.

This book is about the impact of that photo. It tells the story of September 7, 1957, the day the students were turned around at the schoolhouse door. It talks about the local school board, whose moderate members were replaced by segregationists in the next election, and their attempts to get the courts to delay integration. It covers the lost year where Gov. Faubus, in defiance of the federal government, canceled schools in Little Rock for the entire year rather than allow schools to integrate. And it looks at the aftermath of the struggle to integrate Little Rock Central High School, visiting again with the Little Rock Nine as adults.

Little Rock Girl is an important account of a key event in Civil Rights History, and it is compellingly and sensitively told. The focal point of the photo, Eckford and an angry white girl, Hazel Bryan, seen behind her in the mob screaming racial slurs at her, is explored in detail.

The book later visits Bryan, then known as Hazel Bryan Massery, the villain of the photo, and explains her regret at her actions that day. Six years after this photo was taken, she contacted Eckford to apologize. Decades later, Massery and Eckford met with Counts, the photographer, and had a reconciliation that included a photo of them together.

Little Rock Girl is the kind of book supporters of the Divisive Concepts Law say they want. In remarks about why he rejected the AP African American Studies course for Georgia Students, State Superintendent Richard Woods claimed one of his problems with the course was that it did not provide enough opposing views on Intersectionality and other topics. Little Rock Girl literally does this, giving Massery, the white girl frozen in time as the face of hate, an opportunity to speak for herself beyond the photo. What more could they want in a book about the Civil Rights Movement?

The MCS School Board is super sensitive about sexual content in books, as seen in the purge of selected books from the MHS library last school year, and they can rest easy knowing there is no sex in Little Rock Girl. None. There is violence, because the white mob brought violence with them to Little Rock Central High School during that time period. However, the violence is sensitively and appropriately described and depicted for middle school students. It is not inflammatory in any way.

If the book doesn’t contain sexual content and is not inflammatory, why is it not approved for classroom use in Marietta City Schools? Your guess is as good as ours. (Spoiler alert: we are leaning towards divisive concepts as the reason.) Marietta in the Middle obtained the vetting document and committee ballots through an open records request. Like with the banned books project last school year, outside readers, typically retired teachers and administrators, were paid to read selected books and fill out an External Review Document. A committee then reviewed those documents and voted whether to keep or remove each book.

The External Review Document for Little Rock Girl contains the following quotes:

Under the item, “Sex: any references to private body parts, sexual acts, sexual innuendo and metaphor, acts of sexual violence,” the evaluator wrote, “None.”

Under the item, “Profanity,” the evaluator wrote, “None.”

Under the item, “Race (Racial slurs, Race Issues),” the evaluator wrote, “The words, n—r and negro are used a [sic] several times in quotes from people yelling at the Arkansas nine. It is in historical context, however vile it may be.”

Under the item, “Graphic Violence or Death,” the evaluator wrote, “There is no way to choose violent situation quotes as the whole book is the history of an especially violent time when integration was taking place. The pictures and text are taken right from the pages of history.”

Under the item, “Controversial Issues,” the evaluator wrote, “Some people may take issue with the subject matter because there is a movement to cover up the behavior of the Whites against Blacks during this era. Everything is taken from history, so none of this should be considered controversial.”

The open records documents contained four External Review Ballots from June 7, 2023. On those ballots, three voted yes for Little Rock Girl, and one didn’t have a vote recorded for that book. On a master External Review Ballot that shows vote totals for all the books evaluated, two people voted for the book and four voted against, so it looks like one vote changed from yes to no on the individual ballots to the final ballot. We are still waiting for receipt of our open records request that should include emails that will give us more insight into why some of these books were removed.

Why is this book not allowed in the curriculum for Marietta Middle School? We don’t know either. There’s no sexual content, it is a balanced portrayal of this historic event, and some people on the book committee seem to like it. Maybe violence got it banned? But how can you talk about the integration of Little Rock Central High School or the Civil Rights Movement without talking about the violence of that time period? Besides, The Hunger Games is on the Approved list for 7th Grade students at MMS. Historical first person accounts of violence are not allowed to be taught, but a fictional story about children bludgeoning each other to death for sport is totes okay?

It makes no sense. Which is why it is time for MCS to provide full transparency to parents and the community about the sweeping changes it has made to curriculum in MCS schools. Marietta in the Middle will continue to force transparency through open records requests until the district learns to do the right thing by parents on its own.

Parents have a right to know what is included in their children’s classrooms, and they also have a right to know what has been removed from those classrooms and why.

Thank you so much for your work in trying to uncover the truth about why this book was banned.